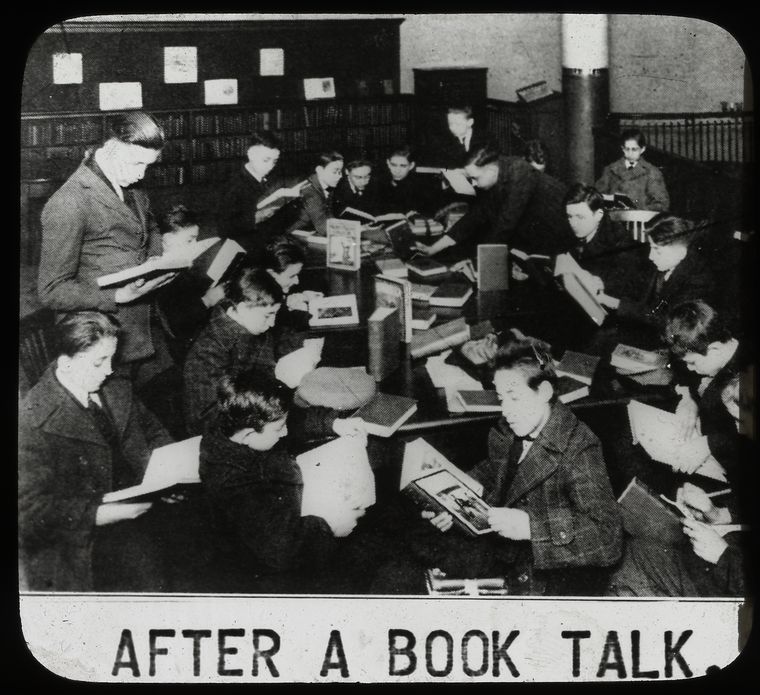

The internet has long offered opportunities to form communities around reading and writing, particularly in the form of fanfiction, which predates the internet but has flourished online. In the 1980s, Usenet groups and email lists were created that focused on fanfiction based on Star Trek and other popular entertainments. FanFiction.net was launched in 1998 and remains popular, with sections for different fandoms such as Harry Potter (the most populated fandom as of August 2015), Dr. Who, and many anime and manga works. It retains something of the look and feel of early web forums.

Wattpad looks very different. It was founded in 2006, a year before Amazon released its Kindle platform, reading device, and store, and the popularity of ebooks surged. From its start, Wattpad has been designed to be a social platform for composing, reading, and sharing responses to stories, all of which are available for free, on the web of through an app. The platform was very much designed with mobile in mind, even though mobile wasn’t as ubiquitous in 2006 as it is today. Though it took a few years to take off, it began to catch the attention of the press in 2012 and now has an astonishing 40 million members worldwide. No wonder it describes itself as “the world’s largest community of readers and writers.”

Based in Canada, it has members across the globe who read and publish stories in more than fifty languages. It’s particularly popular in the Philippines, where the mobile version is reportedly the top-ranked mobile app. At this point it is a privately held corporation supported mainly by venture capital, though some relatively new brand sponsorships (in which Wattpadders are commissioned to write stories about new films, music, or products) may also be part of its business model. The product’s assets, like most social media platforms, is its membership and information about their interests and the popularity of the content they share. Unlike Facebook, though, it doesn’t have a “real names” policy and does not seem to be tying those metrics to other data sources, though it encourages sharing stories through social media and has recently developed a function for turning quotations from stories into graphics to share on Twitter. It’s hard to say how exactly it will make money, since the sauce is secret and the company is in that peculiar phase that new tech platforms go through that some people call “pre-revenue audience building.” Another term might be “magical thinking,” but who’s going to argue with the site’s impressive metrics?

According to venture capital researcher Mary Meeker’s latest Internet Trends report, as of May 2015 (see slide 63 of her presentation), Wattpad had 40 million unique visitors monthly, twice as many as last year, with 11 billion minutes spent on it per month (up 83 percent over last year), ninety percent of this busy activity via mobile phones. In each minute that passes, another 24 hours-worth of text to read is posted. But not all of the members are writers; a company official told Digital Book World last year that 90 percent of the members are readers, not authors.

Dubbed “a YouTube for stories” and likened to Instagram, it’s a youthful site in style and tone, but one of its most prominent promoters is Margaret Atwood, who sees it as democratizing of literacy. In a 2012 Guardian article, she wrote,

No one need know how old you are, what your social background is, or where you live. Your readers can be anywhere. And if you’re worried about adverse reactions from your teachers, your grandmother, or others who might not like you writing about slavering zombies or your relatives, you can use a pseudonym.

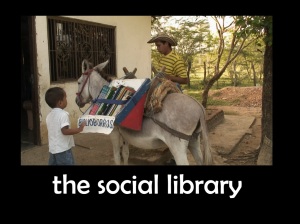

She does not see this kind of story-sharing as competition for traditional publishers, but rather a bridge to them. More importantly, she sees Wattpad as a path to literacy in an unequal world. You can’t always buy ebooks if you don’t have enough money – or, like many Wattpadders, aren’t old enough to have a credit card. Nor do all aspiring writers around the globe have access to writing tools and models to emulate.

Our generation in the west was lucky: we had readymade gateways. We had books, paper, teachers, schools and libraries. But many in the world lack these luxuries. How do you practice without such tryout venues? Without a piano, how do you learn to play the piano? How can you write without paper and read without books? . . . Wattpad opens the doors and enlarges the view in places where the doors are closed and the view is restricted. And somewhere out there in Wattpadland, a new generation is testing its wings.

Adventures in Convergence Culture

I joined Wattpad nine months ago and began to poke around. After exploring the social features and reading a few stories, I dusted off an old floppy disk with a young adult time-travel story I’d written in the early 1990s and posted it serially, as most Wattpad stories appear, one chapter at a time over the course of several weeks, to get to know both the platform and the nature of its interactions better. (I had to make a few changes, including a new opening from which the story could become a flashback. I have a feeling a huge proportion of Wattpad members weren’t born when I wrote that thing and wouldn’t recognize a floppy disk. Also, yes, it is deeply weird to read something you wrote so long ago envisioning a future with limited surveillance capabilities – hah, I wish! – but I digress.) I can’t say my experiment yielded much in terms of insight into the social life of Wattpad for writers. There is a lot of competition for attention and, as many members advise in various “how to do Wattpad” guidebooks, writers need to spend a lot of time engaging with others before they will be discovered, and I didn’t. But even with this limited engagement, I can make some observations.

First, the platform is great for writing. On a desktop, it’s a clean and intuitive interface that gives writers a distraction-free writing space. No, it doesn’t have all the features of Word, but most writers rarely need those fiddly bits. I found the clean, simple interface refreshing. The phone app can also be used as a writing space (if your thumbs are up to it), which is likely the most common writing method among younger members of the site who may not have access to a laptop or simply are used to composing on a phone. For me, the app enabled easy editing when I spotted a typo or missing word. The default setting for copyright is “all rights reserved” (which someone who uploaded Shakespeare plays carelessly left in place) but the platform also offers a variety of Creative Commons licenses.

Though the writing space is stripped-down simple, Wattpad offers ways to visually enhance a story. Writers can create and upload covers created DIY, by using a separate Wattpad app, or through a kind of barter system that I don’t thoroughly understand. Apparently some graphic arts-inclined members create covers for others and their work is acknowledged in dedications, which are frequently appended to chapters of stories to recognize other members. Writers can also add pictures or videos as chapter headers, and frequently do. Chapters are sometimes introduced or closed with a comment from the author encouraging suggestions, promising a timeline for the next installment, or begging readers to be patient because exams are looming and they won’t have time to post another chapter anytime soon.

The distance between readers and writers and between the story and the person who wrote it are deliberately blurred in this environment. There is a sense that works are in progress and readers and writers experience the unfolding of a story together. Writers also get a sense of affirmation when readers comment on their work or ask for more. Generally the comments are not the incisive analysis that writers would get from an editor or from comrades in a writing workshop. They tend to be short expressions of pleasure, responses to what’s happening in the story (“Whoa!!” “Nooooooo!”), or gestures of identification. (“That happened to me.” “That’s my birthday, too!” “My brother acts exactly like this guy.”) This seriality and intimate form of sharing owes much to fanfiction culture and is well depicted in Rainbow Rowell’s young adult novel, Fangirl.

There are metrics on every chapter and on your profile, constant reminders of how many people follow you, how many have looked at your stories, and how many comments and votes you’ve received. All of these pings of attention are meant to be positive. As one of the founders, Allen Lau, explained to Publisher’s Weekly, novice writers crave affirmation and so all of the cues give positive reinforcement. There are no downvotes here. Scanning through stories that I added to my library, I found virtually no negative comments. Instead, these notes are generally short, flippant, and supportive. Comments that don’t conform to community standards can be flagged by anyone for deletion.

Though it’s an amazingly cheerful and positive place, it is also part of the attention economy. Those visible metrics are a display of status, which creates a certain undercurrent of anxiety about getting reads. Comments to community boards are sometimes desperate pleas for readers or requests for advice about how to get more followers and reads. Popular writers, whose status is reinforced by being featured on the discovery page, get tens of thousands of views, or in some cases millions, or even as many as a billion views, as Anna Todd did with a series that riffed on the boy band One Direction, the kind of fanfiction celebrity that led to the insanely popular and ultimately profitable 50 Shades trilogy, a fanfiction based on Twilight. (As an aside, all three blockbusters seem to revolve around abusive relationships. I wonder what that’s about?) Whether Todd’s book contract or film deal will pay off is unknown, the kind of blockbuster bet that big entertainment likes to place. These days, both self-publishing and sites like Wattpad have become crowd-sourced slushpiles for traditional publishers. As for Anna Todd, who kept her (pre-edited) books freely available on Wattpad, the affirmation that she gets from the social features of the platform are a necessary part of writing. As she told a reporter for The New York Times, “the only way I know how to write is socially and getting immediate feedback on my phone.”

Some member/writers have been chosen to be “ambassadors” – moderators with specific duties that keep the community harmonious, but who are presumably paid only in the feels. There are also community sections of the site. Clubs are where members can talk about improving their writing, graphic design, the publishing industry, genres, or anything at all in “The Café.” There are also areas for awards, contests, #justwriteit (a place where members can commit to writing and get inspiration, rather like National Novel Writing Month), and a recently-launched section for writers on how to use the site and get writing tips. There is also a page of information on a new program, “Wattpad Stars.” It’s not clear how writers become stars, but this program pairs Wattpadders with brands, mostly entertainment industry heavy-hitters, but including Unilever, which promoted a facial cleanser to teens in the Philippines by commissioning a story in Tagalog by a Wattpadder. Though paid product placement is rare in traditional publishing, this venture is an interesting way to blend fanfiction’s love of engaging with commercial culture and the use of Wattpad by its members as a bridge from free sharing to more commercial pursuits.

My second major impression from using the site is that it’s a great place for readers, particularly young readers who enjoy fanfiction, romance stories, or young adult fiction. There are loads of other genres, too, but these seem most popular. You can discover books the hard way, by browsing genre categories or searching the tags authors assign their works, or you can click on the books covers that appear whenever you open the app – some new, some popular, some selected by Wattpad staff, some that appear, after you’ve chosen some stories, to be algorithmically chosen to match your previous choices. Each time you choose a book, you also get “you may also like” choices. All of these books are free, and they stay on your phone even when you’re offline. They are also often quite compelling to read and composed with narrative sophistication. Of course, there are stories that are full of clichés and rehashing of tired tropes, but that’s true in all kinds of publishing. What astonished me was how polished so many of the stories are.

Like users of the Kindle (which came into the world after Wattpad but, with Amazon’s enormous reach, ramped up much more quickly), Wattpad readers can experience instant gratification, the reassurance that they have something to read with them all the time, and a seemingly bottomless pool of books to choose from. Unlike Kindle, these books are free, and the social apparatus in which they are nestled is youthful, supportive, and ubiquitous. Amazon, generally a nimble company, tried late in the game to get a foot in the fanfiction door with Kindle Worlds, a place where writers can create and sell fanfiction – but only for certain willing brands, and only if they follow stringent guidelines and are willing to license some uses to the product they are riffing on and if they give Amazon world publication rights for the duration of copyright (meaning until long after you’re dead). It does not seem to have taken off in a big way. I suspect there are two kinds of “free” missing, here – free to readers and free for writers to do what they like.

What’s interesting at Wattpad is that it’s infused with the free-wheeling remixing and community-building spirit of fanfiction while also including mild warnings about copyright. Wattpad has had to remove copyrighted material, and cautions writers not to use copyrighted works in the images or videos they choose for chapter headings, but that warning is blithely ignored by many Wattpadders who remix and repurpose as if they were born to it – as, in fact, many of them were.

From the perspective of examining online reading communities, Wattpad is fascinating. Some of the socializing is unabashedly promotional. Writers engage in hopes that readers will engage with them. But a lot of it is the kind of informal chatter and friendship-building that revolves around shared reading experiences. I didn’t see any in-depth criticism or analysis, but that isn’t the point.

The point is sharing emotional responses to the work and the act of reading it: Love love love. Intense! Actual tears. Whaaa… did that just happen? Update pls. Having those reactions serially, immediately, and in the company of others within a web of social relationships is a very contemporary version of the decades-old practice of talking about books online.

Posted by Barbara

Posted by Barbara