I found The Case of Lisandra P. by Hélène Grémillon to be powerful, disturbing, and difficult to read for more than one reason. The cover claims it’s a page-turner, but the only time I turned pages quickly was when I honestly couldn’t handle what the author was putting in front of me. Otherwise, it took me a while to commit to it because it seemed to be about a therapist accused of murdering his wife whose only ally is a patient who tries hard to be remote and unlikable. I tend to avoid reading stories that advance through transcriptions of therapy sessions because too often it’s a lazy device to provide insight into a character (usually a messed-up cop doing messed-up things who we’re supposed to sympathize with) and the first of these sessions made me wonder if I should be reading something else. But the second session had an irresistible hook in it for someone who likes crime fiction to involve social issues. The book is set a few years after Argentina returned to “democracy” after a brutal military dictatorship that made dissidents disappear violently and without a trace (sometimes seizing their children and raising them, perversely, as their own, passing on their distorted and vile worldview to innocents). During the time this book is set, the government has decided to put all that behind them by essentially pardoning everyone involved and giving them anonymity. The main character has been seeing the therapist to deal with the trauma of her daughter’s disappearance, in large part because she has no idea whether people around her who seem so benign may have actually tortured and killed her daughter. The novel provides an appropriately chilling sense of how dreadful that would be. It also provides a neatly tied-up and ironic ending that upends the idea that there is any way to give a story about this time and place a sense of resolution. There was a certain amount of sensationalism in the ending that felt off to me for reasons I can’t explain without a spoiler, but everything between the opening pages and the closing ones seemed brutally true – a kind of truth that offers no reconciliation, because there was none.

I found The Case of Lisandra P. by Hélène Grémillon to be powerful, disturbing, and difficult to read for more than one reason. The cover claims it’s a page-turner, but the only time I turned pages quickly was when I honestly couldn’t handle what the author was putting in front of me. Otherwise, it took me a while to commit to it because it seemed to be about a therapist accused of murdering his wife whose only ally is a patient who tries hard to be remote and unlikable. I tend to avoid reading stories that advance through transcriptions of therapy sessions because too often it’s a lazy device to provide insight into a character (usually a messed-up cop doing messed-up things who we’re supposed to sympathize with) and the first of these sessions made me wonder if I should be reading something else. But the second session had an irresistible hook in it for someone who likes crime fiction to involve social issues. The book is set a few years after Argentina returned to “democracy” after a brutal military dictatorship that made dissidents disappear violently and without a trace (sometimes seizing their children and raising them, perversely, as their own, passing on their distorted and vile worldview to innocents). During the time this book is set, the government has decided to put all that behind them by essentially pardoning everyone involved and giving them anonymity. The main character has been seeing the therapist to deal with the trauma of her daughter’s disappearance, in large part because she has no idea whether people around her who seem so benign may have actually tortured and killed her daughter. The novel provides an appropriately chilling sense of how dreadful that would be. It also provides a neatly tied-up and ironic ending that upends the idea that there is any way to give a story about this time and place a sense of resolution. There was a certain amount of sensationalism in the ending that felt off to me for reasons I can’t explain without a spoiler, but everything between the opening pages and the closing ones seemed brutally true – a kind of truth that offers no reconciliation, because there was none.

I very much enjoyed Sigurðardóttir’s The Silence of the Sea, winner of the 2015 Petrona  Award. Though I’ve enjoyed several volumes in her Thóra Gudmundsdóttor series, I was especially taken with her ghost story, I Remember You, where the author gives her penchant for the spooky and unexplained free rein. I’m not at all a fan of the horror genre, so I was surprised how much I enjoyed that atmospheric story that has a mystery to solve, but puts the unexplainable first. In The Silence of the Sea, we get the best of both kinds of story. Thóra has to untangle the estate of a family who has vanished at sea – or presumably at sea. Nobody knows for sure, because the yacht they were sailing on has arrived on shore with its crew and passengers missing. As she pursues this task, trying to find out what happened so that she can sort out the affairs of the missing couple and their two daughters to take care of a third, much younger daughter left at home in Iceland with her distraught grandparents, we go aboard the yacht from its departure in Portugal out to the vast, empty sea, learning exactly what happened to each of the people aboard. It’s a kind of claustrophobic Christie-style mystery with supernatural effects, all of which have rational explanations for the mystery reader who hates jiggery-pokery, but with plenty of suspense and creepiness for those who think there’s more to it. The psychology of the people on board is intensely developed, the chapters in Iceland provide a welcome respite, there’s the social backdrop of a small island nation reeling from a catastrophic financial collapse, and the whole thing works quite well, along with a disturbing ending that’s . . . well, I’ll just leave it there.

Award. Though I’ve enjoyed several volumes in her Thóra Gudmundsdóttor series, I was especially taken with her ghost story, I Remember You, where the author gives her penchant for the spooky and unexplained free rein. I’m not at all a fan of the horror genre, so I was surprised how much I enjoyed that atmospheric story that has a mystery to solve, but puts the unexplainable first. In The Silence of the Sea, we get the best of both kinds of story. Thóra has to untangle the estate of a family who has vanished at sea – or presumably at sea. Nobody knows for sure, because the yacht they were sailing on has arrived on shore with its crew and passengers missing. As she pursues this task, trying to find out what happened so that she can sort out the affairs of the missing couple and their two daughters to take care of a third, much younger daughter left at home in Iceland with her distraught grandparents, we go aboard the yacht from its departure in Portugal out to the vast, empty sea, learning exactly what happened to each of the people aboard. It’s a kind of claustrophobic Christie-style mystery with supernatural effects, all of which have rational explanations for the mystery reader who hates jiggery-pokery, but with plenty of suspense and creepiness for those who think there’s more to it. The psychology of the people on board is intensely developed, the chapters in Iceland provide a welcome respite, there’s the social backdrop of a small island nation reeling from a catastrophic financial collapse, and the whole thing works quite well, along with a disturbing ending that’s . . . well, I’ll just leave it there.

A third book that I read recently is Canadian and features a Muslim detective investigating a cell of radical Islamists and, along the way, the various ways that Canadians from different backgrounds negotiate creating a society together. It also probes the utterly different interpretations of Islam held by the protagonist, Esa Khattak, and a charismatic extremist. I reviewed The Language of Secrets by Ausma Zehanat Khan for Reviewing the Evidence, reposting it here thanks to RTE’s generous policies.

A third book that I read recently is Canadian and features a Muslim detective investigating a cell of radical Islamists and, along the way, the various ways that Canadians from different backgrounds negotiate creating a society together. It also probes the utterly different interpretations of Islam held by the protagonist, Esa Khattak, and a charismatic extremist. I reviewed The Language of Secrets by Ausma Zehanat Khan for Reviewing the Evidence, reposting it here thanks to RTE’s generous policies.

Following her well-received debut, THE UNQUIET DEAD, Khan continues an intriguing series focused on a Canadian detective of Afghan heritage who heads a federal community policing task force in Toronto created to deal with sensitive cases in a multicultural nation. His experience in both homicide and intelligence work makes him uniquely qualified to investigate the murder of a Muslim man who was working undercover when he traveled with a group to a remote part of a provincial park, apparently to train for a terrorist attack.

Hassan Ashkouri, the leader of an ultra-conservative mosque, has created two cells of adherents who gather together to discuss theology, politics, poetry, and possibly creating mayhem. Among those adherents are a young disaffected Somali-Canadian rapper, his waifish punk girlfriend, and a crabby convert named Paula who is looking for meaning in her life (while being infatuated with the charismatic if scary Ashkouri). Soon they are joined by another young woman exploring Islam – Esa Khattak’s colleague, Rachel Getty. She has followed the murdered man into the heart of the mosque to find out who killed him – and why he had decided to disobey his orders.

The investigation is challenging, but it’s made far more difficult as an intelligence official, Ciprian Coale, withholds information and deliberately impedes Khattak’s work, thanks to a longstanding grudge and a suspicion that Khattak’s religious beliefs make him somehow less Canadian. (Some of the interagency complexity would be easier to grasp by reading the previous book in the series.) To complicate matters, Khattak’s strong-willed sister Ruksh has become engaged to Ashkouri, believing him to be a devout and honorable man. Khattak and Getty don’t have time to lose. Intercepts indicate that there will be some sort of attack to mark the new year.

Khattak understands the missing context that explains so much of current events: the history of colonialism, the repeated disappointments as democratic movements have been crushed, the subtleties of a religion misrepresented in the news and by Wahhabi-inspired demagogues, inflamed as western societies tilt toward bigotry and right-wing nationalism. While Ashkouri uses poetry a kind of code to conceal his plans, Khattak invokes it when thinking about how complex his world is:

The generations mislaid by decades of war, by centuries of struggle.

The splintered past, the crippled future, nothing to gain, less to give.

A bruised carnation planted in a cup . . .

A knotting of sinews and bone because you were never disconnected from what the ummah suffered, any more than you could understand the madmen who claimed to speak or kill or die in their name.

This mystery, like its hero, is cerebral, but develops tension as time grows short and Rachel’s cover grows tattered. Khattak’s nuanced understanding of his religion and of the present moment steadies him as he and his partner Rachel strive to serve “a nation of communities, bound together by the things they hold in common.”

You may or may not have noticed, all three of these books are by women; one is by a woman of color. My next challenge will be to expand the diversity of my reading, an issue Sisters in Crime is currently working on for its upcoming Summit Report. I think it’s going to provide both practical help for writers (and readers) who would like to see a publishing industry that is more reflective of the general population as well as a rousing argument for why reading (and publishing) diverse books matters. Meanwhile, I’ve been collecting links about diversity in publishing and am keeping an eye out for more.

Do you have mysteries by authors of color (or non-heteronormative authors or authors with disabilities) to recommend? I need to give my reading list more diversity.

Posted by Barbara

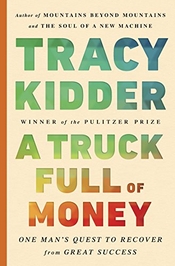

Posted by Barbara  I’ve finished the book (I got a review copy) and have been struggling to review it because I have the very same reservations Joshua expresses here. I love Kidder’s work. The Soul of a New Machine got at a certain culture with a lot of focus and depth. Home Town looked at lives in a college town – not a single culture at all, but exploring its many sides. Mountains Beyond Mountains was a portrait of a man driven to make the world a healthier, more just place. The trouble for this reader started when Kidder says he wanted to bookend his Soul of a New Machine to show the world of people who write software. As in his other books, he finds someone who can give him a close third person view, a shoulder to peer over. But while he does a good job of telling us about this person, in the end we never know much about the experience of (or the culture of) coding, which makes it hard to find the book’s soul, it’s motivation. It does bear out

I’ve finished the book (I got a review copy) and have been struggling to review it because I have the very same reservations Joshua expresses here. I love Kidder’s work. The Soul of a New Machine got at a certain culture with a lot of focus and depth. Home Town looked at lives in a college town – not a single culture at all, but exploring its many sides. Mountains Beyond Mountains was a portrait of a man driven to make the world a healthier, more just place. The trouble for this reader started when Kidder says he wanted to bookend his Soul of a New Machine to show the world of people who write software. As in his other books, he finds someone who can give him a close third person view, a shoulder to peer over. But while he does a good job of telling us about this person, in the end we never know much about the experience of (or the culture of) coding, which makes it hard to find the book’s soul, it’s motivation. It does bear out

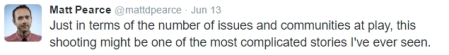

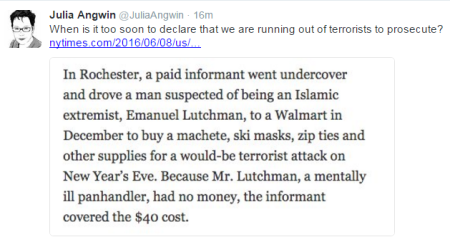

simply disgruntled and unwary people have been persuaded by paid informants to say they would do stupid things that they wouldn’t have without official encouragement – and by the ways that we are all under unprecedented mass surveillance by both the state and by corporations.

simply disgruntled and unwary people have been persuaded by paid informants to say they would do stupid things that they wouldn’t have without official encouragement – and by the ways that we are all under unprecedented mass surveillance by both the state and by corporations. I found The Case of Lisandra P. by Hélène Grémillon to be powerful, disturbing, and difficult to read for more than one reason. The cover claims it’s a page-turner, but the only time I turned pages quickly was when I honestly couldn’t handle what the author was putting in front of me. Otherwise, it took me a while to commit to it because it seemed to be about a therapist accused of murdering his wife whose only ally is a patient who tries hard to be remote and unlikable. I tend to avoid reading stories that advance through transcriptions of therapy sessions because too often it’s a lazy device to provide insight into a character (usually a messed-up cop doing messed-up things who we’re supposed to sympathize with) and the first of these sessions made me wonder if I should be reading something else. But the second session had an irresistible hook in it for someone who likes crime fiction to involve social issues. The book is set a few years after Argentina returned to “democracy” after a brutal military dictatorship that made dissidents disappear violently and without a trace (sometimes seizing their children and raising them, perversely, as their own, passing on their distorted and vile worldview to innocents). During the time this book is set, the government has decided to put all that behind them by essentially pardoning everyone involved and giving them anonymity. The main character has been seeing the therapist to deal with the trauma of her daughter’s disappearance, in large part because she has no idea whether people around her who seem so benign may have actually tortured and killed her daughter. The novel provides an appropriately chilling sense of how dreadful that would be. It also provides a neatly tied-up and ironic ending that upends the idea that there is any way to give a story about this time and place a sense of resolution. There was a certain amount of sensationalism in the ending that felt off to me for reasons I can’t explain without a spoiler, but everything between the opening pages and the closing ones seemed brutally true – a kind of truth that offers no reconciliation, because there was none.

I found The Case of Lisandra P. by Hélène Grémillon to be powerful, disturbing, and difficult to read for more than one reason. The cover claims it’s a page-turner, but the only time I turned pages quickly was when I honestly couldn’t handle what the author was putting in front of me. Otherwise, it took me a while to commit to it because it seemed to be about a therapist accused of murdering his wife whose only ally is a patient who tries hard to be remote and unlikable. I tend to avoid reading stories that advance through transcriptions of therapy sessions because too often it’s a lazy device to provide insight into a character (usually a messed-up cop doing messed-up things who we’re supposed to sympathize with) and the first of these sessions made me wonder if I should be reading something else. But the second session had an irresistible hook in it for someone who likes crime fiction to involve social issues. The book is set a few years after Argentina returned to “democracy” after a brutal military dictatorship that made dissidents disappear violently and without a trace (sometimes seizing their children and raising them, perversely, as their own, passing on their distorted and vile worldview to innocents). During the time this book is set, the government has decided to put all that behind them by essentially pardoning everyone involved and giving them anonymity. The main character has been seeing the therapist to deal with the trauma of her daughter’s disappearance, in large part because she has no idea whether people around her who seem so benign may have actually tortured and killed her daughter. The novel provides an appropriately chilling sense of how dreadful that would be. It also provides a neatly tied-up and ironic ending that upends the idea that there is any way to give a story about this time and place a sense of resolution. There was a certain amount of sensationalism in the ending that felt off to me for reasons I can’t explain without a spoiler, but everything between the opening pages and the closing ones seemed brutally true – a kind of truth that offers no reconciliation, because there was none. Award. Though I’ve enjoyed several volumes in her Thóra Gudmundsdóttor series, I was especially taken with her ghost story, I Remember You, where the author gives her penchant for the spooky and unexplained free rein. I’m not at all a fan of the horror genre, so I was surprised how much I enjoyed that atmospheric story that has a mystery to solve, but puts the unexplainable first. In The Silence of the Sea, we get the best of both kinds of story. Thóra has to untangle the estate of a family who has vanished at sea – or presumably at sea. Nobody knows for sure, because the yacht they were sailing on has arrived on shore with its crew and passengers missing. As she pursues this task, trying to find out what happened so that she can sort out the affairs of the missing couple and their two daughters to take care of a third, much younger daughter left at home in Iceland with her distraught grandparents, we go aboard the yacht from its departure in Portugal out to the vast, empty sea, learning exactly what happened to each of the people aboard. It’s a kind of claustrophobic Christie-style mystery with supernatural effects, all of which have rational explanations for the mystery reader who hates jiggery-pokery, but with plenty of suspense and creepiness for those who think there’s more to it. The psychology of the people on board is intensely developed, the chapters in Iceland provide a welcome respite, there’s the social backdrop of a small island nation reeling from a catastrophic financial collapse, and the whole thing works quite well, along with a disturbing ending that’s . . . well, I’ll just leave it there.

Award. Though I’ve enjoyed several volumes in her Thóra Gudmundsdóttor series, I was especially taken with her ghost story, I Remember You, where the author gives her penchant for the spooky and unexplained free rein. I’m not at all a fan of the horror genre, so I was surprised how much I enjoyed that atmospheric story that has a mystery to solve, but puts the unexplainable first. In The Silence of the Sea, we get the best of both kinds of story. Thóra has to untangle the estate of a family who has vanished at sea – or presumably at sea. Nobody knows for sure, because the yacht they were sailing on has arrived on shore with its crew and passengers missing. As she pursues this task, trying to find out what happened so that she can sort out the affairs of the missing couple and their two daughters to take care of a third, much younger daughter left at home in Iceland with her distraught grandparents, we go aboard the yacht from its departure in Portugal out to the vast, empty sea, learning exactly what happened to each of the people aboard. It’s a kind of claustrophobic Christie-style mystery with supernatural effects, all of which have rational explanations for the mystery reader who hates jiggery-pokery, but with plenty of suspense and creepiness for those who think there’s more to it. The psychology of the people on board is intensely developed, the chapters in Iceland provide a welcome respite, there’s the social backdrop of a small island nation reeling from a catastrophic financial collapse, and the whole thing works quite well, along with a disturbing ending that’s . . . well, I’ll just leave it there. A third book that I read recently is Canadian and features a Muslim detective investigating a cell of radical Islamists and, along the way, the various ways that Canadians from different backgrounds negotiate creating a society together. It also probes the utterly different interpretations of Islam held by the protagonist, Esa Khattak, and a charismatic extremist. I reviewed The Language of Secrets by Ausma Zehanat Khan for

A third book that I read recently is Canadian and features a Muslim detective investigating a cell of radical Islamists and, along the way, the various ways that Canadians from different backgrounds negotiate creating a society together. It also probes the utterly different interpretations of Islam held by the protagonist, Esa Khattak, and a charismatic extremist. I reviewed The Language of Secrets by Ausma Zehanat Khan for  be accurate, my rage at the way the surveillance-industrial complex has taken over our world. It’s a weird convergence of Silicon Valley values (free is a low, low price; just make micropayments of personal information every time you touch a keyboard) and Big Brother collect-it-all arrogance. It’s telling that the government couldn’t implement its overreaching

be accurate, my rage at the way the surveillance-industrial complex has taken over our world. It’s a weird convergence of Silicon Valley values (free is a low, low price; just make micropayments of personal information every time you touch a keyboard) and Big Brother collect-it-all arrogance. It’s telling that the government couldn’t implement its overreaching