So, if my sabbatical proposal is accepted, it won’t happen until the 2014-15 academic year, but I had fun outlining a project that I’m actually excited about (and think I may still be excited about 18 months from now). I want to immerse myself in online reading communities.

But you already do that, you say? Yes, I do. But this would be my excuse to do more of it, and to look a bit more closely at how readers talk about books on a variety of platforms and think about what this means for readers, authors, libraries, and publishers in a world where reading is global (and publishing contracts remain local). It ties into my resistance to algorithmic marketing messages and the commodification of our identities in a socially networked, hyper-commercialized world. It’s also my opportunity to highlight how savvy crime fiction readers are and how that deep communal knowledge base can tell scholars something wise about literature and the reading experience.

Also, I want to experiment with the ways scholars could communicate now that we don’t have to rely on traditional mechanisms. I think scholarship is valuable, and not just of interest to a tiny sliver of like-minded specialists (or, if it is only that, those specialists shouldn’t expect the rest of us to foot the bill for their inward-gazing research written up for an audience of six or ten; you all can hash it out amongst yourselves, okay?) So fair warning: I’m going to be all exhibitionist and post stuff here and elsewhere in case anyone else is interested. If you aren’t – no worries. I am not in this for the “likes.”

One thing that makes me sad is that I originally imagined flying over to the UK to meet Maxine Clarke, because what she did to promote online discussion of mysteries was one of the inspirations for this project, and her extraordinary background in scientific publishing would have made her a terrific cultural informant. Unhappily, I waited too long – but her presence in our global reading community has been a major influence on this project of mine.

Anyway, here’s the proposal I’m sending in, in case anyone is interested. Wish me luck.

—–

Sabbatical Proposal

Barbara Fister

March 11, 2013

I would like to spend my next sabbatical working on a digital humanities project with two purposes: (1) to conduct research into online reading communities and (2) to present my findings in ways that explore alternatives to traditional scholarly publishing.

(1) Social Reading Practices Online

There hasn’t been much research to date on online communities of avid readers that have formed to discuss books and the reading experience together. Their existence has become more visible with the advent of the GoodReads social network, which currently has over 14 million members, as well as its older, geekier cousin LibraryThing (1.5 million members). The rise of Amazon as a vertically-integrated book industry powerhouse is also an example of a platform that mixes commerce and voluntary book discussion and interaction between readers and authors, though controversies erupt periodically over review sock-puppetry and reviewer rankings (e.g. Pinch & Kessler 2011, Steitfeld 2012).

However, online reading communities date back to the early days of the Internet, with Usenet groups such as rec.arts.mystery (formed in the 1980s), Listserv groups, such as Dorothy-L (founded at Kent State University in 1990), and thousands of Yahoo and Google groups devoted to books that have formed in the past three decades. Such communities provide intriguing sites for researchers to explore what group members get out of reading for pleasure, observe the social aspects of reading, and witness how informal critical communities participate in the formation of cultural tastes around books. They also are places to observe social interactions in a digital space, including the negotiation of difference and the evolution of group social norms. Finally, they provide a vantage point for observing the ways people integrate their online and IRL (in real life) identities and can offer opportunities to consider cultural attitudes about digital versus face to face social interactions.

It will also be interesting to explore the emergence of new social platforms and their effect on online communities. Web 2.0 – the interactive web that includes blogs, Facebook, Twitter, and other media – contains contradictory impulses. On the one hand, these platforms provide “free” spaces for interactivity and self-expression. On the other, they are designed around the self as a commodity. Personal information about habits, tastes, and interpersonal connections becomes valuable raw material platforms gather for data aggregation, mining, and resale. Individuals participating in these networks, in turn, are encouraged to market themselves and measure their social capital through the attraction of friends, likes, comments, retweets, and other quantitative analytics build into the platforms. I am curious about how these built-in analytics, which encourage self-representation in terms of marketing and promotion, influence reader group formation and social regulation. I am also interested in the role authors play in this space which is a mix of social interaction and self-promotional marketing work.

I plan to focus my study on readers of crime fiction, primarily because I am already a long-term participant in a number of online groups focused on that genre. I expect to use interviews, surveys, participant-observation and other primarily qualitative research methods. In addition to submitting my research plans to the IRB, I will refer to the recommendations for ethical research developed by the Association of Internet Researchers (2012) to ensure that I gather and use information ethically. I anticipate addressing an interlocking set of questions which will likely include the following lines of inquiry.

- What are the social dimensions of reading and how does online reading group participation compare to the groups studied by Elizabeth Long (2003)?

- Do the experiences of avid readers who participate in online groups confirm or depart from Catherine Sheldrick Ross’s findings (1999)?

- How does online group participation enhance the reading experience for participants? How do those benefits compare to face-to-face reading groups?

- What are the demographics of online reading groups? Who participates? How does age and gender figure in group composition? Are there some platforms that younger readers prefer, and if so, why?

- What social rules emerge within a group? Are they explicit and is the group moderated? If not, how does the group handle trolls or heated disagreements? What kinds of relationship work do members perform to overcome a breach of group norms? How do they welcome new members?

- How do members of online reading groups learn about new books that might interest them? “Discovery” is a compelling problem for publishers, who in the past relied on physical distribution to reach markets with sales reps and booksellers playing a key role. What can readers online tell us about the discovery process in a world saturated with choices?

- How do authors and readers interact in these groups and how do readers and authors negotiate the difference between peer relationships and commercial relationships?

- Is the author-reader relationship changing authorship itself (as Stephanie Moody has suggested)? How does what Henry Jenkins calls “convergence culture” affect writers who interact regularly with their reading base?

- How are avid readers reading today? What affordances contribute to the choices they make about print versus e-books or among e-book platforms? How device-agnostic are they? What do they think about the rights issues articulated by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (2010)?

- Given that reader communities are borderless, what does membership in these communities contribute to greater understanding of other cultures?

- How do readers experience rights restrictions, territorial sales, and (in cases such as the Australian book market) protectionist policies that limit access to books across borders? As discovery outpaces access, what are the implications for the book business?How do avid readers tap into local book culture? Does online engagement with books parallel local patronage of bookstores, libraries, author events, and other book-related cultural practices?

- What are the advantages and constraints facing avid readers in different countries? (I will likely focus primarily on readers in the US, UK, and Australia, but may also study the experience of readers in Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa, since their economic, cultural, linguistic, and social situations make for distinctive book cultures – and they all have a lively presence in online communities.)

- What roles do brick-and-mortar bookstores, public libraries, and fan conventions play in the lives of genre readers?

- For readers who engage in multiple social media platforms, what distinctions do they draw between them? What features appeal to them as readers, or are seen as drawbacks?

- What is the history of discussing books online? How have the platforms for interaction changed, and what impact have those changes had on participants?

- In an era of dwindling review space in traditional media, how have these reading communities, (including online review sites and book bloggers) provided an alternative? How well do these alternative media work for those making reading choices?

- How does the kind of criticism performed in these public places intersect with literary criticism, if at all? Do avid readers provide a depth of knowledge about genres that has critical value? What do scholars of literature have to learn from fan culture?

- What contribution can this work make to the ongoing debates about digital culture enjoined by critics of technophilia such as Nicholas Carr, Jaron Lanier, Sherry Turkle, and Evgeny Morozov, as well as more utopian views of digital networks found in the work of David Weinberger, Yochai Benkler, and Clay Shirky? What can the study of online reading communities contribute to our understanding of the interplay between digital culture and culture in general?

(2) New Approaches to Sharing Scholarship

This project, because of its digital focus and its multiple potential audiences, would provide a good opportunity to play with new ways of communicating scholarship. I propose making this a totally open project, with the questions that arise, speculations, dead ends, and conclusions available publicly and open for comment at every step of the way. I see the audience for this work to be not just other scholars (though I hope it will make a contribution to the scholarship around popular literacy, genre fiction, reading, and digital culture) but a cross-section of readers, publishers, writers, fans, and anyone interested in the book and its future.

Toward that end, I want to make this work accessible to these various audiences, both in terms of how I express myself (blending my scholarly interests with more vernacular approaches to genre literature and the act of reading) and in terms of who has actual access. For the past few years, I have been actively involved in the open access movement. In recent years I have only published my scholarship in venues which are open to all, either because there are no fees for access or because the publishers’ contracts allow self-archiving. (In fact, my entire department pledged in 2009 to make our work open access; we were the first liberal arts college to pass a departmental open access mandate.) Free access means more than a low, low price. It is an approach to scholarship that is open to discussion and available for others to repurpose. (See Suber, 2012, for a clear discussion of the distinction between gratis and libre open access.) I have followed and participated in experiments in open peer review such as Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s Planned Obsolescence with interest. I would like to make this project public from the start and invite contributions and comments from members of my multiple communities: readers, writers, publishers, critics, digital humanists, librarians. I am not sure at this point exactly what form this public work will take, but if this sabbatical project is approved, I envision beginning a series of interactions using social media such as Twitter (which is home to a lively digital humanities community) FriendFeed, old-school online reading networks that use groups and listservs, single-author platforms which invite comments (blogging), a public web archive of any relevant documents, a public bibliography via Zotero, and perhaps ultimately a book-length anthology or compilation of findings. If I create such a culminating document, I will likely use an open source platform such as PressBooks. I plan to use the most open Creative Commons license available for all of this work to invite remixing and reuse.

In many ways, the two parts of this project knit together my various interests in a satisfyingly complementary way. Knowing how communities of readers interact online will have implications for the lifelong learning goals we have for our students, who tend to see research as a set of academic tasks to be completed according to spec rather than as participation in an ongoing conversation. I have been trying, with mixed success, to introduce students to using blogs and other social media for invention, curation, discovery, and expression. I worry that we introduce them to only a piece of what it means to do research. They can find and use sources when needed, but they are not necessarily prepared to follow up on new developments in an area of interest, participate in professional digital communities, or apply their writing skills and intellectual training to public expression using social media. I have used blogs in classes for eight years and have not seen much increase in students’ familiarity with the technological and design capabilities of social platforms or in students’ ability or inclination to keep their eyes open for interesting things going on in the world. They are much happier if given a prompt to respond to rather than being asked to look around for something intriguing to write about. I’m sure time pressures contribute to this aversion for frequent informal and improvisatory invention, but being curious and able to develop personal filters to scan and sort through new information is a skill worth cultivating that is largely neglected in our pedagogy.

I’m also invested in the future of trade and scholarly publishing. We’re on the cusp of sweeping changes, and librarians need to step up and be part of the solution. Trade publishing matters because books are a significant record of our culture. Leaving its future in the hands of major publishers or Amazon – corporations more focused market share than on sharing or preserving culture – would be a betrayal of library values and a serious problem for future scholars who may have no public cultural record to consult. Scholarly publishing is ripe for new models and repurposing library resources and skills to help with the transition seems more important than finding yet new ways to wring more temporary licensed access to knowledge out of shrinking budgets. Finally, as the humanities face challenges from public figures who are hostile to education that is not firmly tethered to workforce readiness (and who fail to see how very much the humanities do, in fact, prepare their future hires to think, communicate, organize, and lead), I am committed to making research public and to do what I can to break down the barriers between academia and “the real world.” I’m hoping this project might help me discover some models for sharing and inviting participation in scholarship as it develops that others may find useful.

Though it may seem arcane to study readers’ responses to a particular slice of genre fiction, a case could be made that it’s in these cultural environs that we can find common ground between everyday readers and scholarly approaches to culture. We might even discover that they’re not as separate as we may think.

Works cited

Association of Internet Researchers. (2012). Ethical decision-making and Internet research: Version 2.0. Retrieved from http://aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: how social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press. This book can be retrieved from http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/wealth_of_networks/

Carr, N. G. (2010). The shallows: what the Internet is doing to our brains. New York: W.W. Norton.

Electronic Frontier Foundation. (2010, February 16). Digital books and your rights: A checklist for readers. Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.eff.org/wp/digital-books-and-your-rights

Fitzpatrick, K. (2011). Planned obsolescence. New York: New York University Press. The Media Commons version of the crowd-reviewed manuscript can be retrieved from http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/mcpress/plannedobsolescence/

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press.

Lanier, J. (2010). You are not a gadget: A manifesto. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Long, E. (2003). Book clubs: Women and the uses of reading in everyday life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moody, S. (2011) Virtual relations: Exploring the literary practices of ecommunities. Paper presented at the Conference on College Composition and Communication Annual Conference, Atlanta, April 2011.

Morozov, E. (2013). To save everything, click here: The folly of technological solutionism. New York: PublicAffairs.

Pinch, T. & Kesler, F. (2011). How Aunt Ammy got her free lunch. Retrieved from http://www.freelunch.me/filecabinet

Sheldrick Ross, C. (1999). Finding without seeking: The information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management,35(6), 783-799.

Shirky, C. (2010). Cognitive surplus: Creativity and generosity in a connected age. New York: Penguin Press.

Streitfeld, D. (2012, December 22). Giving mom’s book five stars? Amazon may cull your review. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/23/technology/amazon-book-reviews-deleted-in-a-purge-aimed-at-manipulation.html?smid=pl-share

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. New York: Basic Books.

Weinberger, D. (2007). Everything is miscellaneous: The power of the new digital disorder. New York: Times Books.

Selected past publications related to this project

On student learning

“The library’s role in learning: Information literacy revisited,” Library Issues (March 2013): 33.4.

“Wikipedia and the challenge of read/write culture.” (2007, January). Library Issues 27.3

“The Devil in the Details: Media Representation of ‘Ritual Abuse’ and Evaluation of Sources.” (2003, May). SIMILE: Studies in Media and Information Literacy Education 3.2.

“Teaching the rhetorical dimensions of research.” (Fall 1993). Research Strategies 11.4: 211-219.

On reading

“Reading, risk, and reality: Undergraduates and reading for pleasure,” with Julie Gilbert, College & Research Libraries 72.5 (September 2011): 474-495.

“‘Reading as a contact sport’: Online book groups and the social dimensions of reading.” Reference and User Services Quarterly, 44.4 (Summer 2005): 303-309.

On publishing

“The public versus publishers: How scholars and activists are occupying the library.” Anthropologies 12 (March 2012).

“Liberating Knowledge: A Librarian’s Manifesto for Change.” Thought & Action (Fall 2010): 83-90.

“Trade publishing: A report from the front.” (2001). portal: Libraries and the Academy 1.4: 509-523.

On crime fiction

“The millennium trilogy and the American serial killer narrative: Investigating protagonists of men who write women” (2012). In Rape in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy and Beyond: Contemporary Scandinavian and Anglophone Crime Fiction edited by Berit Åström, Katarina Gregersdotter and Tanya Horeck. London: Palgrave: 34-50.

“Copycat Crimes: Crime Fiction and the Marketplace of Anxieties.” Clues: A Journal of Detection 23.3 (Spring 2005): 43-56.

image courtesy of Social Collider – a screenshot of some of my Twitter connections in the past month. I’m not sure what it means, but it’s pretty.

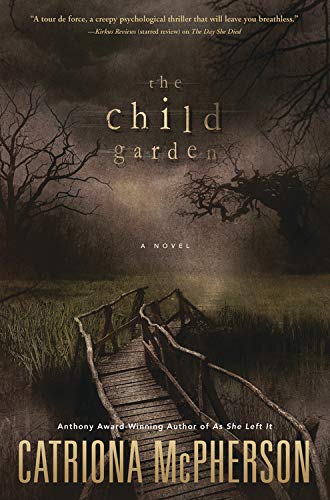

fascinating setting, and a moving relationship between the narrator and her severely disabled son. Gloria lives in a tumble-down house lent to her by an elderly woman who lives nearby in the same care home as the boy. Instead of rent, Gloria must take care of a rocking stone, a large bolder trapped in a gap that rocks when you push it; the old woman is insistent that Gloria keep the rock secret and gently push it every day a certain number of times without saying why it’s so important. After Gloria finishes the day’s work as a “registrar” (a public official who keeps records of births, marriages, and deaths) she visits the care home and reads Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses to her disabled son. (I doubt I’ll ever read those poems again without remembering how strangely ominous they are in this story.) An old school friend who left to attend an alternative school called Eden that briefly occupied the Victorian building that now houses the care home turns up abruptly with a strange story about being stalked by a troubled schoolmate who . . . well, it seems things have not gone well for the students who attended Eden, and Gloria is determined to find out exactly what’s going on. Though I did have an inkling who was responsible for the disturbing goings on, I really enjoyed this story, particularly for the combination of the narrator’s Scottish voice and for the fiercely protective and tender relationship she has with her son. Kudos to the publisher, Midnight Ink, for a job well done. I think it would be grand if all publishers started their life as booksellers.

fascinating setting, and a moving relationship between the narrator and her severely disabled son. Gloria lives in a tumble-down house lent to her by an elderly woman who lives nearby in the same care home as the boy. Instead of rent, Gloria must take care of a rocking stone, a large bolder trapped in a gap that rocks when you push it; the old woman is insistent that Gloria keep the rock secret and gently push it every day a certain number of times without saying why it’s so important. After Gloria finishes the day’s work as a “registrar” (a public official who keeps records of births, marriages, and deaths) she visits the care home and reads Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses to her disabled son. (I doubt I’ll ever read those poems again without remembering how strangely ominous they are in this story.) An old school friend who left to attend an alternative school called Eden that briefly occupied the Victorian building that now houses the care home turns up abruptly with a strange story about being stalked by a troubled schoolmate who . . . well, it seems things have not gone well for the students who attended Eden, and Gloria is determined to find out exactly what’s going on. Though I did have an inkling who was responsible for the disturbing goings on, I really enjoyed this story, particularly for the combination of the narrator’s Scottish voice and for the fiercely protective and tender relationship she has with her son. Kudos to the publisher, Midnight Ink, for a job well done. I think it would be grand if all publishers started their life as booksellers. Rubbernecker by Belinda Bauer – A very good thriller with an unusual hero: a young man with Asperger’s who is fascinated by dead things, for reasons that gradually become clear as we get to know him. He follows his passion by taking a course in anatomy and physiology, joining medical students as they dissect cadavers. In another plotline, we learn about a man injured in a car accident who can’t communicate with his carers but grows increasingly concerned that someone means him harm. At times creepy and often suspenseful, I ultimately found the story touching and quite compelling.

Rubbernecker by Belinda Bauer – A very good thriller with an unusual hero: a young man with Asperger’s who is fascinated by dead things, for reasons that gradually become clear as we get to know him. He follows his passion by taking a course in anatomy and physiology, joining medical students as they dissect cadavers. In another plotline, we learn about a man injured in a car accident who can’t communicate with his carers but grows increasingly concerned that someone means him harm. At times creepy and often suspenseful, I ultimately found the story touching and quite compelling. embattled cop and a feminist social activist who consults with the police on crimes against women. In this case, a large cache of human remains is uncovered on Gallows Hill, where executions were once held; but one of the skeletons is relatively new … These are good books, with a lot of action and two compelling lead characters, but the real star is South Africa itself, a complex and troubled country trying to reinvent itself.

embattled cop and a feminist social activist who consults with the police on crimes against women. In this case, a large cache of human remains is uncovered on Gallows Hill, where executions were once held; but one of the skeletons is relatively new … These are good books, with a lot of action and two compelling lead characters, but the real star is South Africa itself, a complex and troubled country trying to reinvent itself.

Posted by Barbara

Posted by Barbara

would probably have enjoyed it a smidge more on paper).

would probably have enjoyed it a smidge more on paper).